LEONARD COHEN - The Last Interview (September 2016)

https://youtu.be/H4PqY-VgSsI

Published on Nov 10, 2016

David Remnick from The New Yorker shared yesterday his last interview with Leonard Cohen on September 2016.

Leonard

Cohen, who died last week aged 82, was an inspiration to a host of

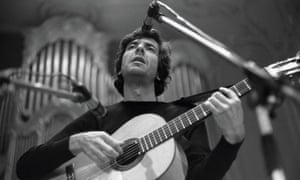

artists over five decades. Here we remember a troubadour of the spirit:

Cohen’s lugubrious tones always divided opinion; for some they were intrinsic to his melancholic charms, to others a turn-off that blindsided them to the genius of his songcraft, which was always gilded, its cadences measured, its images polished. “They’ve filed me under gloom,” he would later complain. Yet Cohen’s gloom was usually consoling, and brought a wry wisdom to his principal focus, affairs of the heart. Anyone who has gone through a painful bust-up will find Closing Time a close companion, especially that line, “It looks like freedom but it feels like death”. Touche.

Contrary to the justified acclaim on which he bows out, Cohen was not always so revered. The opening trilogy of albums, which contains anthems like Suzanne, Sisters of Mercy, Bird on A Wire and Famous Blue Raincoat, barely troubled the US charts (they fared far better in the UK, where Leonard became the bedsit bard of choice).

The half-dozen albums he delivered in the 70s and 80s were even more a hit-free zone, addressed principally by critics, aficionados and Cohen’s fellow musicians, who knew a good song when they heard one. Numerous – often inspired – covers of his work helped seal Cohen’s reputation. Judy Collins, Joe Cocker and Nina Simone were early champions. Later, in the early 90s, a pair of tribute albums crewed by everyone from REM and Bono to John Cale helped reawaken interest. Hallelujah alone boasts 300 covers, including Jeff Buckley’s sepulchral 1994 take, which became a hit in 2007.

Hit-free yet somehow omnipresent – someone, somewhere was always playing one of his songs – Cohen occupied a singular position in rock culture. Older by a decade than most of his peers, he came with a former life as a literary pin-up in his native Canada, arriving with two books of poetry before delivering two “poetic” novels, The Favourite Game and Beautiful Losers, by the mid-60s. He had spent time on the Greek island of Hydra, where he bought a house with a $1,500 bequest, and lived the life of a lotus-eater, sporting a white suit to quaff red wine at the taverna, dropping acid with his partner Marianne Ihlen, writing songs and entertaining luminaries such as beat poets Allen Ginsberg and Gregory Corso.

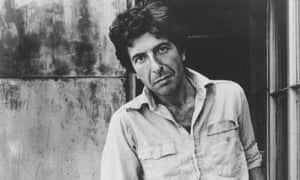

Photograph: Roz Kelly/Getty Images

Cohen admitted to experimenting with drugs “recreational, obsessional and pharmaceutical”, but as he grew older his refuge from the depression that had dogged him since childhood was most often red wine and beautiful women. His decade-long relationship with artist Suzanne Elrod broke up in 1979, leaving two children, Adam and Lorca, with whom Leonard remained close. Cohen’s persona in this middle passage was as a dapper roué, captured by the title of 1977’s Death of A Ladies’ Man, for which Elrod took the cover shot. The album itself proved a low point in his career, wildly misproduced by a gun-waving Phil Spector.

I’m Your Man (1988) was an act of reinvention, pushing the songs into more socially engaged territory. Who else would have attempted a dialogue between Joan of Arc and the fire that consumed her (Joan of Arc, 1971). His songs increasingly explored a philosophy that could underpin the art of living. Religion and spirituality were in the family – his great-grandfather had founded Montreal’s first synagogue – and Cohen became song’s most accomplished spiritual quester.

He never abandoned the Jewish faith, but Christianity and Buddhism were a powerful presence in his life and work; from 1990 he spent five years in a zen monastery atop California’s icy Mount Baldy. As a pop psychopomp, Cohen has often been compared to Bob Dylan – arguments about who is the better poet rage in the wake of Dylan’s Nobel prize; Cohen thought the award “like pinning a medal on Everest for being the highest mountain” – but while Dylan has most often played avenging Old Testament prophet (even when he was a Christian), Cohen has always pursued compassion and redemption. “Love’s the only engine of survival,” as he put it in The Future (1992), an otherwise dystopian vision that shows he could also give the devil his due.

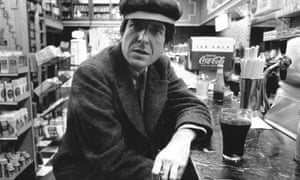

Photograph: K&K Ulf Kruger OHG/Redferns

To put himself and his failing health through the military campaign of a world tour testifies to Cohen’s strength, his delight, his commitment to his art; and in You Want It Darker, like David Bowie’s Blackstar, we are left with a powerful missive from the very brink of death.

Leonard Cohen pulled it all off with his customary elan, the old suavity inherited from his haberdasher father – “Darling, I was born in a suit,” he told biographer Sylvie Simmons. Besuited, betrilbied and beloved, he’ll always be our man.

https://www.theguardian.com/music/2016/nov/13/leonard-cohen-remembered-appreciation-neil-spencer

No comments:

Post a Comment